EN

EN

Who knows, perhaps it will be you and your team that will achieve the highest results.

Who knows, perhaps it will be you and your team that will achieve the highest results.We also want to remind you that in order to simplify the search for players and teams, we have updated our eSports website and added a special section in which teams search for players, and players search for teams.

Tournament rules

- Ranks: First Sergeant — Legend

- The team consists of 7 players.

- In battle – 5 tankers from each team.

- Your garage doesn’t matter as battles are played in Sport mode.

- On the battlefield, in each team, hulls and turrets should not be repeated. For example, if you use Hornet and Ricochet, no one else from your team should be in the battle with Ricochet or Hornet.

- More detailed rules can be found on the tournament page on the eSports portal.

Prizes

- TMR points

- Unique «Impulse» paint

- 96,000 Rubies

- 88,000,000 crystals

- 2,835 epic keys

- 1,071 days of «Premium Pass»

Tournament dates

- Tournament registration will last from 13:00 UTC on January 12th till 17:00 UTC on January 25th.

- The first match will start on January 26th.

- The tournament will end before February 19th.

- The transfer is open and will last until 17:00 UTC on January 25th.

The tournament will be attended by 32 to 128 teams.

Almost immediately after the first rating tournament, we will announce the second one and after all the rating tournaments there will be a Major one. In the Major tournament, they will fight not only for in-game rewards, but also for real cash.

Go to the eSports portal, create your team, read the rules, register and get ready for the next rating tournament! And if you have any questions, visit our eSports Discord server, they will definitely help you.

See you on the battlefields and eSports broadcasts!

Event dates: January 16th, 2 AM UTC — February 6th, 2 AM UTC.

Bots

During the festival, bots in Matchmaking battles will be equipped with special equipment: Freeze, Gauss, Hammer, and Magnum, with the skins from the ICE series!

Now it will be easy to distinguish them from common players!

Discounts

Take advantage of the beneficial discounts from January 16th to January 19th.

For 3 whole days, you will be able to obtain the following items with a 30% discount:

Special Event Modes

During the event, we’ve prepared three special modes for you.

«Dragon’s gold» — one of the players is equipped with the «Juggernaut» super tank

- Iran MM

- Kungur MM

- Magistral MM

This is the game mode for Tanki virtuosos! In addition to well-aimed Grenade throws, you also need well-aimed Railgun shots. An accurate shot at a thrown Grenade and there will be no trace left of your enemy. Shoot, detonate, and win!

- Sandbox Remastered

- Sandal Remastered

- Cross Remastered

Crush enemies with BO-NK in the updated team mode and catch a lot of gold boxes, because this weekend, we have increased their dropping frequency!

- Canyon PRO

- Garder PRO

- Pass PRO

Special offers

What’s any holiday without some great deals at awesome prices?

January 16th — February 2nd

January 16th — February 6th

** For 30 days, each day the player can access a pre-completed mission upon logging in, from which they can claim a reward of 150 Rubies.

Note: One-time purchase

January 23rd — February 6th

January 30th — February 6th

Epic Containers

- SKIN Railgun UT

- SKIN Ares XT

- Railgun’s “Round Destabilization” augment

- Railgun’s “«Death Herald» Compulsator” augment

- Railgun’s “Excelsior” augment

- Ares’ “Excelsior” augment

- Ares’ “Grenadier” augment

- And everything you can get from Common Containers

Special Missions

We have prepared a plethora of exciting missions that will make the event more exciting!

Part 1. January 16th — January 23rd

Part 2. January 23rd — January 30th

Part 3. January 30th — February 6th

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

January 16th — February 6th

TASK

Complete «Come in! Part 1», «Good Reputation. Part 1», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 1», «Frostbite. Part 1», «Cold-Hearted. Part 1», «Freezer. Part 1», «Warm Place», «Ice Shield», «Permafrost», «Shards» and «Ice Stash» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in CP mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use boosted armor 150 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 experience points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 4000 crystals in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Open 15 any Containers.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

January 23rd — February 6th

TASK

Complete «Come in! Part 2», «Good Reputation. Part 2», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 2», «Frostbite. Part 2», «Cold-Hearted. Part 2», «Freezer. Part 2», «Snow Massacre», «Snow Trap», «North Star», «Snowstorm» and «Inevitability» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in TDM mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use mines 150 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 45 stars in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 30 tanks in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Deal 100000 damage in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

January 30th — February 6th

TASK

Complete «Come in! Part 3», «Good Reputation. Part 3», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 3», «Frostbite. Part 3», «Cold-Hearted. Part 3», «Freezer. Part 3», «Northern Flag», «Cold Treatment», «Preemptive Play», «Shock Freeze» and «Spread» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in CTF mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use repair kit 150 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 1 tank using grenades in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 10 tanks using critical damage in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use any grenade 10 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Advent Calendar

We are launching the festive advent calendar for you!

After purchasing the “Advent Calendar” special offer, you will get access to:

- 5 standard missions

- 1 Supermission with unique rewards!

All you need to do is log into the game during the event and claim your gifts.

Task: Complete all “One More Day” missions that appear after January 16th.

Completing 5 standard missions will unlock the final Supermission.

Supermission

One more day

Elite Pass

The most luxurious pass is here! It will consist of 20 levels.

Your goal is to earn stars and unlock new levels, and for each level you reach, you will receive additional prizes!

In order to complete the whole pass and reach the main prize, you will need to earn 1000 stars.

All stars earned during the event will be counted. Progress begins with the start of the event. Stars earned before the purchase of the «Elite Pass» will also be counted. The «Elite Pass» itself is required to claim the prizes. By purchasing it, you will be able to claim all the unlocked prizes to your Garage!

The Main Prizes are Legendary Key ×1 and the “Excelsior” augment for Hornet!

The price of this «Elite Pass» is 2300 Rubies.

Festive Decorations

- Festive paint on cargo drones

- Festive paint

- Festive Gold Box drop zone skin

- Special loading screen

- Festive billboards

Great mood and good luck to everyone!

From December 26th 2 AM UTC until January 22nd 2 AM UTC, we will launch the “Tanki and The Snow Trap” mini-game on a special site. You will conquer drifting ice floes and receive special prizes!

To get your tank to move between those ice floes, your tank will need fuel — Gingerbread.

Gingerbreads

These are the special event currency. You can track the number of your units of Gingerbread reserves on the mini-game interface.

Here are the ways that you can get Gingerbread:

- Completing special event missions — 12 units of Gingerbread

- From special Gold Boxes — 1 unit of Gingerbread

- Completion of Contracts

Contracts

A Contract is a mission that requires earning reputation points in Matchmaking battles.

Contracts can be purchased from December 26th, 2 AM UTC until January 21st, 2 AM UTC in the Shop for Crystals or Rubies.

After the purchase, open the “Contracts” section in the “Missions” menu and activate the contract.

There are 3 types of contracts in the event:

Reward: Gingerbread х2; Bronze Contract х1

One-time purchase

- Time to complete: until January 21st, 2 AM UTC

- Time to collect the prize: until January 21st, 2 AM UTC

- Alternative reward if not completed in time: Crystals х1000

- Alternative reward if the reward is not collected in time: Crystals х1000

- Early completion price: Rubies 300-1

- Time to complete: until January 21st, 2 AM UTC

- Time to collect the prize: until January 21st, 2 AM UTC

- Alternative reward if not completed in time: Crystals х49900

- Alternative reward if the reward is not collected in time: Crystals х49900

- Early completion price: Rubies 300-1

- Time to complete: until January 21st, 2 AM UTC

- Time to collect the prize: until January 21st, 2 AM UTC

- Alternative reward if not completed in time: Rubies х290

- Alternative reward if the reward is not collected in time: Rubies х290

- Early completion price: Rubies 1500-1

IMPORTANT information:

- You can only have 1 contract activated at one time.

- If you have already completed the contract requirement and earned 5000 reputation points, the reward should be claimed immediately, otherwise a new contract cannot be activated.

- At the end of the event, if you completed a contract, but didn’t claim its reward, you can receive an alternative reward depending on the contract’s price.

- After January 21st, all contracts will become unavailable and expire. They will be marked with a red color.

Before completing a contract, DON’T FORGET to activate it.

How to Start

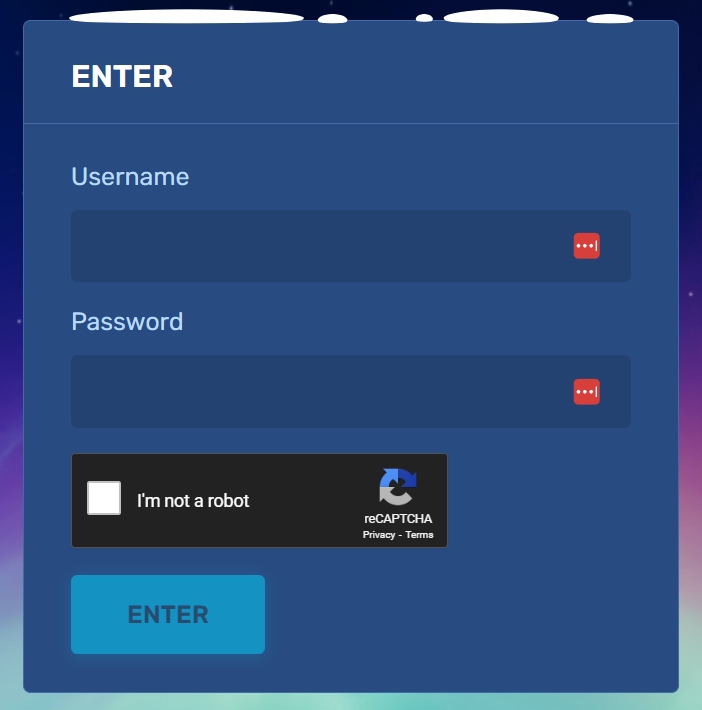

To start your journey, you need to log in to the mini-game website, using the nickname and the password of your in-game account.

Ice Floes

The mini-game map consists of ice floes, and on each of them, a surprise awaits you.

But as you know, there are good and bad surprises:

- Let’s start with the good ones, where you will get: Common Keys, Rare Keys, Epic Keys, an augment for Magnum, ICE skins, and special Grenades. When you conquer an ice floe, a reward is sent to a special storage at the Checkpoint, and is not immediately credited to your in-game account.

- For each move, you need to spend 10 units of Gingerbread. You can move one or two floes forward.

- There will be special “snow traps” on your way. By entering them, you have a 50% chance to either move two steps back or stay in the same place.

Don’t worry, even if luck is not on your side and you get pushed back, you can receive a reward for each ice floe that you pass twice on your way forward.

Checkpoints

A player starts their journey from the 1st Checkpoint. The mini-game ends when you reach the 7th Checkpoint.

After completing a whole lap, the player reaches a checkpoint. There is a special vault on it to store all the prizes that the player received from the ice floes on that lap. When visiting a checkpoint, the player can transfer the prizes from the vault to their in-game account.

Moreover, whenever you reach a checkpoint, you will receive even more unique rewards in your vault.

Prizes

Checkpoint 1

Checkpoint 2

Checkpoint 3

Checkpoint 4

Checkpoint 5

Checkpoint 6

Checkpoint 7

Increases the turret’s rate of fire at the cost of reduced damage per shot.

Shells used by this version of Magnum feature a smaller explosive charge, saving a significant amount of weight. This results in a higher rate of fire, smoother recoil, faster aiming, and a much higher density of fire. The “Carronade” performs noticeably better at close range compared to the standard Magnum.

On the other hand, firing the “Carronade” at maximum range is more demanding and requires greater skill from the shooter.

Special missions with Gingerbreads

Want to get a lot of gingerbreads? Then these missions are for you!

TASK

Destroy 100 tanks using light hulls (Wasp, Hornet, Hopper) in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Destroy 100 tanks using medium hulls (Hunter, Viking, Crusader, Paladin, Dictator) in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Destroy 100 tanks using heavy hulls (Ares, Titan, Mammoth) in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Destroy 100 tanks using melee-range turrets (Firebird, Freeze, Isida, Tesla, Hammer) in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Destroy 100 tanks using medium-range turrets (Smoky, Striker, Vulcan, Thunder, Twins, Ricochet) in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Destroy 100 tanks using long-range turrets (Shaft, Gauss, Magnum, Railgun, Scorpion) in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

Good luck in conquering new heights!

An IC series turret embodies the harsh power of ice. Covered in a thick layer of Antarctic ice, it resembles a dangerous crystalline beast, its form seemingly carved from permafrost. Every shot resonates with merciless cold, leaving an icy trail in its wake and turning the battlefield into a frozen wasteland.

This turret is made for those ready to face the frost head-on and answer their enemies with cold fury.

How to get it

You can obtain the Magnum IC skin at the 7th and final checkpoint of the «Tanki and The Snow Trap» mini-game 2025.

This skin will be a true highlight of your collection and another bonus to your New Year’s mood.

Good luck in battles!

In today’s episode, we will be announcing the new mini-game. We’ll also be giving updated on Classic and wishing you Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

How to get there?

You can get onto “Tanki Classic” only through the announcement window in the main game lobby.

You will only have access if you are an early access participant.

How to get Early Access?

The special Early Access offers for “Tanki Classic” were only available for a limited time. With the start of the mass testing phase, we are bringing these special offers back on sale. This is your chance to become a part of the legendary “Tanki Classic” project ahead of everyone else!

What is there in the game?

This is a test version of the game. It is possible to encounter bugs, issues, unfinished features, and anomalies.

During the test, we will restart the game several times and even temporarily pause the testing process.

We will also wipe the test server database several times, which will reset all your progress.

For testing Tanki Classic, we use new server infrastructure. This may cause unstable server performance during the first weeks of testing. We will be configuring and fixing everything.

Is this early access already?

No. Early access will be announced separately, 2 weeks before the game is released. You will be able to get access to the game earlier than anybody else and progress your account earlier than others.

What is the “Development Plans” section on the Tanki Classic website?

Alongside the launch of Tanki Classic testing, we are adding a special “Development Plans” section to the project’s website. From now on, this section will be the primary, first-source of information on the development of the Tanki Classic project.

There, we will announce the key development areas of the project earlier than anywhere else.

Please note: the presented plans reflect our current goals and may be adjusted based on your feedback and voting results.

In the future, we will launch the promised polls for the game mechanics. You, the players, will define the future of “Tanki Classic!”

Feedback can be left on the forum topic of this news.

It’s time to sum things up and thank the most dedicated helpers of Tanki Online for their selfless work. Those who have been working hard for the entire year for the good of the project. They are our pride, the Best Helpers of 2025.

These tankers made the greatest contribution to the development of the game in 2025: moderating the game resources, keeping information up to date across all platforms, testing updates, reviewing reports, and catching cheaters.

- Marcus

- Spy

- Mosad

- Stealth

- Jack

- rommeltanki

- Yele

- Vlad

- Elegante

- Dynasty

- natrolite

- Lennard

- NikmanGT

- fjrenke

- Sabry

- Ghost

- Mr_STIFFLER

- fjrenke

- Super_Nickson

- Seraphina

- Future

- Hans

- Bartson74

- Dumbledore6969

- chinufire

- Mr.Skiil

- Edu_Gamer

- Helax

- Positive

- Scientist

- Squirrellover

- Nocturn

- Peruere

- zam

- Heatw4ve

- wolfson

- BHOOT_KING

- Marekos1111

- Who_Is_NexT

- Legendarni

- k4n

- Walking.Dead

- Mr.Fox

- Spicy_Crabs

- Tornike

- 7ofHearts

This year has been bright and full of action: exciting events, major updates, intense battles, and countless memorable moments. You became an essential part of everything that happened, and we kept working hard to make the game even better for you.

A new year means new goals, new victories, and new opportunities. Together, we’re ready to reach new heights!

May 2026 bring you inspiration, joyful discoveries, cozy moments with loved ones, and lots of reasons to smile. We wish you health, happiness, good luck, and success both in the game and in real life!

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year! 🎄✨

The event will last from December 19th, 2 AM UTC till January 16th, 2 AM UTC.

Bots

For the duration of the celebration, all bots in Matchmaking battles will turn into snowmen!

Now they can be easily distinguished from real players!

Epic Containers

In honor of the celebration, they are filled with lots of augments and shot effects!

Contents:

- NEW “Detonator” augment for Railgun

- “Excelsior” augment for Firebird

- “Excelsior” augment for Freeze

- “Excelsior” augment for Isida

- “Excelsior” augment for Tesla

- “Excelsior” augment for Hammer

- “Excelsior” augment for Twins

- “Excelsior” augment for Ricochet

- “Excelsior” augment for Vulcan

- “Excelsior” augment for Smoky

- “Excelsior” augment for Striker

- “Excelsior” augment for Thunder

- “Excelsior” augment for Scorpion

- “Excelsior” augment for Magnum

- “Excelsior” augment for Railgun

- “Excelsior” augment for Gauss

- “Excelsior” augment for Shaft

- “Excelsior” augment for Wasp

- “Excelsior” augment for Hopper

- “Excelsior” augment for Hornet

- “Excelsior” augment for Viking

- “Excelsior” augment for Crusader

- “Excelsior” augment for Hunter

- “Excelsior” augment for Paladin

- “Excelsior” augment for Dictator

- “Excelsior” augment for Titan

- “Excelsior” augment for Ares

- “Excelsior” augment for Mammoth

- “Blaster” shot effect for Twins

- “Blaster” shot effect for Ricochet

- “Magic” shot effect for Railgun

- And everything that can be obtained from Common Containers

Significantly increases the damage and explostion radius of a Grenade in case of a combo shot. For the combo shot, you must hit your own Grenade with a Railgun shot.

A successful combo detonation of a Grenade requires many conditions to align. The enemy must be at the right distance, the Grenade must be ready, and the turret must be charged. This rarely happens. It’s even rarer to successfully hit the Grenade to trigger the detonation. With this Augment, your efforts will be rewarded many times over.

All you need is one successful hit. Just one successful hit and the enemy’s will shall be shattered.

50% Discounts

Don’t miss the opportunity to make good use of the unbelievable discounts!

From December 19th until December 22nd, 50% discounts await you!

For three whole days, you will be able to obtain the following items with a 50% discount:

Special Event Modes

Four exciting game modes will be waiting for you in the game!

Each tanker is automatically equipped with the special «Snowman» turret. Yes, it shoots snowballs! Join battles in the Deathmatch mode and show your skills!

- New Year 2025 Remastered

Deathmatch. Everyone wants to catch as many gold boxes as possible, risking being left without any loot in a fight with other players.

- New Year 2025 Remastered

- Forest MM Winter NY Remastered

- Sandbox MM Winter NY Remastered

There can be no winter festivities without a snowball fight! The special festive «Snowballs» mode returns on the new special Christmas Remastered map!

- Cross MM Winter Remastered

- Forest MM Winter Remastered

- Sandbox MM Winter Remastered

Dive into an icy warfare! To win, you need to freeze out all opponents and capture points on the map. Be prepared for harsh conditions and a frigid battle!

- Polygon PRO

Special Missions

We have prepared a plethora of exciting missions which will make the event more exciting!

Part 1. December 19th — December 26th

Part 2. December 26th — January 2nd

Part 3. January 2nd — January 9th

Part 4. January 9th — January 16th

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

Set 1. December 19th — January 16th

TASK

Complete «Welcome! Part 1», «Respect! Part 1», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 1», «Well-Deserved Rest. Part 1», «Team Competition. Part 1», «Wish Fulfillment. Part 1», «The Ice Battle», «Santa’s Wrath», «For Everybody », «Polar Star» and «Unboxing! Part 1» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in TDM mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use boosted damage 150 times in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Deal 100000 damage in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 45 stars in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Open 15 any Containers.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Set 2. December 26th — January 16th

TASK

Complete «Welcome! Part 2», «Respect! Part 2», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 2», «Well-Deserved Rest. Part 2», «Team Competition. Part 2», «Wish Fulfillment. Part 2», «Snow Fortress», «Slippery Slope», «Santa’s Treasure», «Firecracker» and «Unboxing! Part 2» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in SGE mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use speed boost 150 times in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 4000 crystals in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use any grenade 10 times in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Open 15 any Containers.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Set 3. January 2nd — January 16th

TASK

Complete «Welcome! Part 3», «Respect! Part 3», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 3», «Well-Deserved Rest. Part 3», «Team Competition. Part 3», «Wish Fulfillment. Part 3», «Who Stole Christmas?», «Ice Shield», «From Year to Year», «Elves’ Revenge» and «Unboxing! Part 3» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in CTF mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use boosted armor 150 times in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 experience points in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 30 tanks in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Open 15 any Containers.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Set 4. January 9th — January 16th

TASK

Complete «Welcome! Part 4», «Respect! Part 4», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 4», «Well-Deserved Rest. Part 4», «Team Competition. Part 4», «Wish Fulfillment. Part 4», «King of the Hill», «Cold Therapy», «Surprise!», «New Year Hassle» and «Unboxing! Part 4» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in CP mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use repair kit 150 times in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 1 tank using grenades in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Complete 15 Daily missions.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Complete 3 Weekly missions.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Special Offers

What’s any holiday without some great deals at awesome prices?

December 19th — January 12th

December 19th — January 16th

** For 30 days, each day the player can access a pre-completed mission upon logging in, from which they can claim a reward of 150 Rubies.

Note: One-time purchase

December 26th — January 16th

January 2nd — January 16th

January 9th — January 16th

Advent Calendar

We are launching the festive advent calendar for you!

After purchasing the “Advent Calendar” special offer, you will get access to:

- 5 standard missions

- 1 Supermission with unique rewards!

All you need to do is log into the game during the event and claim your gifts.

Task: Complete all “One More Day” missions that appear after December 19th.

Completing 5 standard missions will unlock the final Supermission.

Supermission

One More Day

Elite Pass

The most luxurious pass is here! It will consist of 20 levels.

Your goal is to earn stars to unlock new levels, and for each level you reach, you will receive additional prizes.

In order to complete the whole pass and reach the main prize, you will need to earn 1000 stars.

All stars earned during the event will be counted. Progress begins with the start of the event. Stars earned before the purchase of the “Elite Pass” will also be counted. The “Elite Pass” itself is required to claim the prizes. By purchasing it, you will be able to claim all the unlocked prizes to your Garage!

The Main Prizes are ×100 Snowball grenades and a LEGENDARY KEY!

The price of this Elite Pass is 2300 Rubies.

Festive decorations

- Festive paint on cargo drones

- Festive paint

- Festive Gold Box drop zone skin

- Special loading screen

- Festive billboards

- Festive bots in MM

- Cookies instead of mines

- New Year Garage

- “HO-HO-HO” audio for Gold Boxes

- Festive skin for the Gold Box

Have a good Festive mood everyone!

Jump to content

Jump to content

Recommended Posts