EN

EN

Who knows, perhaps it will be you and your team that will achieve the highest results.

Who knows, perhaps it will be you and your team that will achieve the highest results.We also want to remind you that in order to simplify the search for players and teams, we have updated our eSports website and added a special section in which teams search for players, and players search for teams.

Tournament rules

- Ranks: First Sergeant — Legend

- The team consists of 7 players.

- In battle – 5 tankers from each team.

- Your garage doesn’t matter as battles are played in Sport mode.

- On the battlefield, in each team, hulls and turrets should not be repeated. For example, if you use Hornet and Ricochet, no one else from your team should be in the battle with Ricochet or Hornet.

- More detailed rules can be found on the tournament page on the eSports portal.

Prizes

- Unique «Prism» paint

- 96,000 Rubies

- 88,000,000 crystals

- 2,835 epic keys

- 1,071 days of «Premium Pass»

- TMR points

Tournament dates

- Tournament registration will last from 17:00 UTC on February 17th till 17:00 UTC on March 1st.

- The first match will start on March 2nd.

- The tournament will end before March 29th.

- The transfer is open and will last until 17:00 UTC on March 1st.

The tournament will be attended by 32 to 128 teams.

Almost immediately after the second rating tournament, we will announce the third one and after all the rating tournaments there will be a Major one. In the Major tournament, they will fight not only for in-game rewards, but also for real cash.

Go to the eSports portal, create your team, read the rules, register and get ready for the next rating tournament! And if you have any questions, visit our eSports Discord server, they will definitely help you.

See you on the battlefields and eSports broadcasts!

The event will last from February 20th, 2 AM till March 16th, 2 AM UTC.

How to take part

In order to take part in the Sakura Blossom event, you first need to walk the path of a warrior. The “Draw of Fate” will assign you one of three factions, and you will need to fight for the greatness of your clan.

Right after buying the offer, you will become a warrior of one of the following factions: “Ninja Cats”, “Samurai Dogs”, or “Ronin Foxes”.

A special website will become available with the start of the event. You will be able to follow the progress of your faction as well as your individual progress there.

Event rules

After the factions are drawn, you will have to fight for victory by collecting as many Coins as possible.

A special event currency, which can be obtained by completing special event missions, purchased in the Shop for crystals, or bought with Rubies as part of Special offers.

Special Missions

Only those who have obtained the special «Draw of Fate» offer have access to these missions.

We have prepared multiple missions, unlocked on every consecutive day of the event, and they will be available until the end of the event. The more missions you complete, the more individual prizes you will win, and thus a higher chance your faction will have for victory!

February 20th 2 AM — March 16th, 2 AM UTC

TASK

Get into the TOP-3 5 times in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Get a new rank. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Be in the winning team of 10 battles in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Earn 30000 crystals in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Destroy 300 tanks in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Destroy 3 tanks using mines in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Capture 1 flag in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Use repair kit 100 times in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Use overdrive 30 times in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

February 20th 2 AM — March 16th, 2 AM UTC

TASK

Use boosted armor 100 times in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Destroy 30 tanks using grenades in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Use mines 100 times in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Use overdrive 20 times in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Use boosted damage 100 times in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Destroy 30 tanks using critical damage in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Use speed boost 100 times in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Use overdrive 10 times in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Deal 50 critical shots in matchmaking battles. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop. IMPORTANT: The mission is only available for «Event Pass» owners.

REWARD

coin

Packs of Coins

You can find packs of Coins in the Shop during the whole duration of the event.

Special Offers

Purchase a special offer and make a significant contribution towards the victory of your faction!

Prizes

There are several prizes, so there’s something to fight for!

Team Progress

The faction of players that obtains the most amount of Coins will win and receive the main prizes — Thunder DK and Hopper DK skins.

In team progress, all the obtained Coins are counted for the current faction that the player is in.

The participation of every tanker is necessary for victory!

Individual Progress

- Each player receives a collection of individual missions. Completing these helps the player move forward in the personal standings.

- The more Coins a player has, the more prizes the player will be able to obtain.

- For each completed mission, upon the completion of the event, a player receives the prizes (all prizes are listed on the website): lots of keys, grenades, mountains of supplies, augments, and a Legendary key.

Shells deal damage in a large radius. Damage is reduced, but the farther the target is from the shell’s impact point, the more damage it receives.

What exactly is inside these shells is unknown. According to one developer, it contains pure liquid vacuum. Be that as it may, the explosion of such a shell deals more damage the farther the target is from the epicenter of the blast.

Significantly increases damage and reduces the fire rate of the turret.

Installation of the high-caliber “Yamato” cannon into the Thunder turret turns every shot into a solemn event. The heavy cannon significantly slows down reload and turret turning speed. However, you can penetrate the armor of a battleship with one shot. This cannon must be treated with maximum attention and respect, adapting the usage tactic.

Let the fight begin!

The event is held by APL Publishing Ltd. in accordance with the General Rules for Promotions and Contests and Event’s Regulation.

In today’s episode, we will be launching the Sakura Blossom event. We’ll also be introducing the improved Boombox map and showing the Teleport grenade.

On top of that, enjoy plenty of special missions packed with valuable prizes and festive decorations to set the mood!

Event dates: February 6th, 2 AM UTC — March 6th, 2 AM UTC.

Discounts

Take advantage of the beneficial discounts from February 6th to February 9th.

For 3 whole days, you will be able to obtain the following items with a 30% discount:

Special Event Modes

During the event, we’ve prepared special modes for you.

«Dragon’s gold» — one of the players is equipped with the «Juggernaut» super tank

- Magistral MM

- Massacre MM

- Osa MM

Deathmatch. Everyone wants to catch as many gold boxes as possible, risking being left without any loot in a fight with other players.

- Station Winter PRO

- Novel Winter PRO

- Gubakha Winter PRO

Don’t miss the special «Old school» mode with Wasp and Smoky auto-equipped and gold boxes will fall more often.

- Arena PRO

- Atra PRO

- Boombox PRO

- Combe PRO

- Deck-9 PRO

- Duality PRO

- Farm PRO

- Hill PRO

- Island PRO

- Magadan PRO

- Ping-Pong PRO

- Short bridge PRO

- Valley PRO

- Wave PRO

- Zone PRO

The standard «Control Points» mode without additional enhancements such as overdrives and drones. Rely only on your basic skills and standard equipment, focus on pure gameplay and tactics!

- Kungur MM

- Magistral MM

- Massacre MM

Special Offers

What’s any holiday without some great deals at awesome prices?

February 6th — March 2nd

February 6th — March 6th

** For 30 days, each day the player can access a pre-completed mission upon logging in, from which they can claim a reward of 150 Rubies.

Note: One-time purchase

February 13th — March 6th

February 20th — March 6th

February 27th — March 6th

Epic Containers

- SKIN Gauss UT

- SKIN Titan GT

- Gauss’ “Boxer” augment

- Gauss’ “Solenoid Cooling” augment

- Gauss’ “Excelsior” augment

- Titan’s “Blaster” augment

- Titan’s “Excelsior” augment

- And everything you can get from Common Containers

Special Missions

We have prepared a plethora of exciting missions that will make the event more exciting!

Part 1. February 6th — February 13th

Part 2. February 13th — February 20th

Part 3. February 20th — February 27th

Part 3. February 27th — March 6th

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

Set 1. February 6th — March 6th

TASK

Complete «The Sun’s First Ray. Part 1», «A Word Outrunning the Wind. Part 1», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 1», «A Walk Along the River. Part 1», «Links of the Steel Chain. Part 1», «The Merchant. Part 1», «Garden of Stones», «Stone Armor», «Flicker of the Celestial Vault», «Every Style, Versatile» and «Chests of Fortune. Part 1» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in CP mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use boosted armor 150 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 45 stars in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 30 tanks in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Open 15 any Containers.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Set 2. February 13th — March 6th

TASK

Complete «The Sun’s First Ray. Part 2», «A Word Outrunning the Wind. Part 2», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 2», «A Walk Along the River. Part 2», «Links of the Steel Chain. Part 2», «The Merchant. Part 2», «Siege of the Monastery», «Energy of Fire», «Crystals of Fate», «Fireball» and «Dragon’s Breath» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in SGE mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use boosted damage 150 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 4000 crystals in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 1 tank using grenades in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use overdrive 10 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Set 3. February 20th — March 6th

TASK

Complete «The Sun’s First Ray. Part 3», «A Word Outrunning the Wind. Part 3», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 3», «A Walk Along the River. Part 3», «Links of the Steel Chain. Part 3», «The Merchant. Part 3», «War of Dynasties», «Energy of Qi», «Experience of Generations», «Dragon’s Kiss» and «Crackle of Firecrackers» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in TDM mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use repair kit 150 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 experience points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 10 tanks using critical damage in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use any grenade 10 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Set 4. February 27th — March 6th

TASK

Complete «The Sun’s First Ray. Part 4», «A Word Outrunning the Wind. Part 4», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 4», «A Walk Along the River. Part 4», «Links of the Steel Chain. Part 4», «The Merchant. Part 4», «Fight of the Dragons», «Faster than Thought», «7 dreams», «Warrior’s Trace» and «Chests of Fortune. Part 2» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in TJR mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use speed boost 150 times in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Complete 3 Weekly missions.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Deal 100000 damage in any matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Complete 15 Daily missions.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Advent Calendar

We are launching the festive advent calendar for you!

After purchasing the “Advent Calendar” special offer, you will get access to:

- 5 standard missions

- 1 Supermission with unique rewards!

All you need to do is log into the game during the event and claim your gifts.

Task: Complete all “One More Day” missions that appear after February 6th.Completing 5 standard missions will unlock the final Supermission.

Supermission

Missions

Elite Pass

The most luxurious pass is here! It will consist of 20 levels.

Your goal is to earn stars and unlock new levels, and for each level you reach, you will receive additional prizes!

In order to complete the whole pass and reach the main prize, you will need to earn 1000 stars.

Important: All stars earned during the event will be counted. Progress begins with the start of the event. Stars earned before the purchase of the «Elite Pass» will also be counted. The «Elite Pass» itself is required to claim the prizes. By purchasing it, you will be able to claim all the unlocked prizes to your Garage!

The Main Prizes are x1 Legendary Key and the “Excelsior” augment for Viking!

The price of this “Elite Pass” is 2300 Rubies.

Festive Decorations

- Festive paint on cargo drones

- Festive paint

- Festive Gold Box drop zone skin

- Festive loading screen

- Festive billboards

Great mood to everyone!

In today’s episode, we will be launching the Lunar New Year event. We’ll also be starting the new V-LOG contest and updating the Tanki Classic Roadmap.

Dates: From January 30th 2 AM to March 16th 2 AM UTC

Let’s get into the details:

How to invite

Referrals are players who you invited to the game.

You need to follow these steps to make a new player your referral:

STEP 1 Your rank should be at least Master Sergeant.

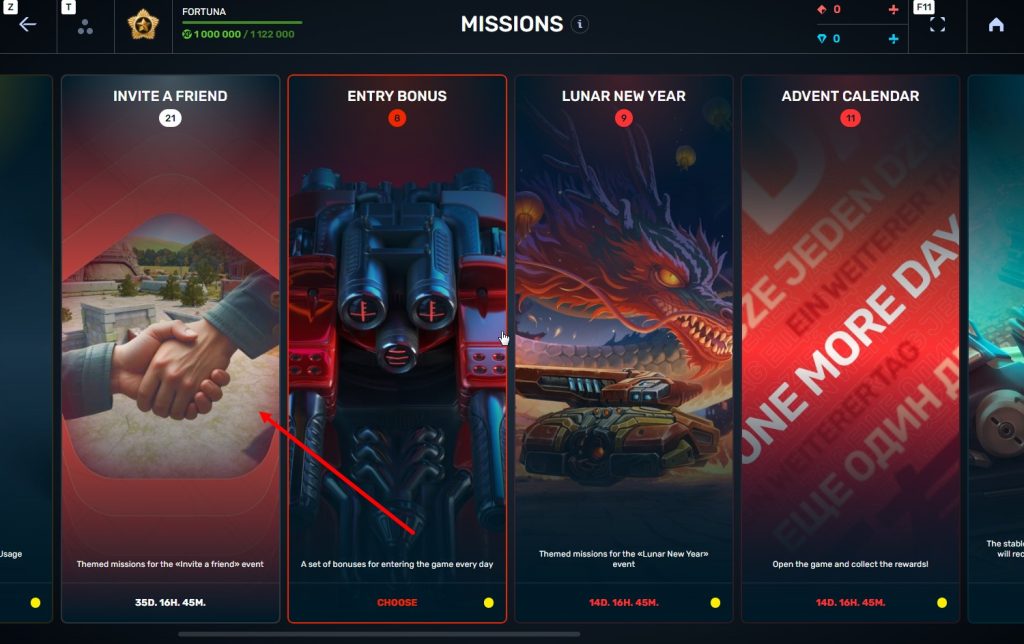

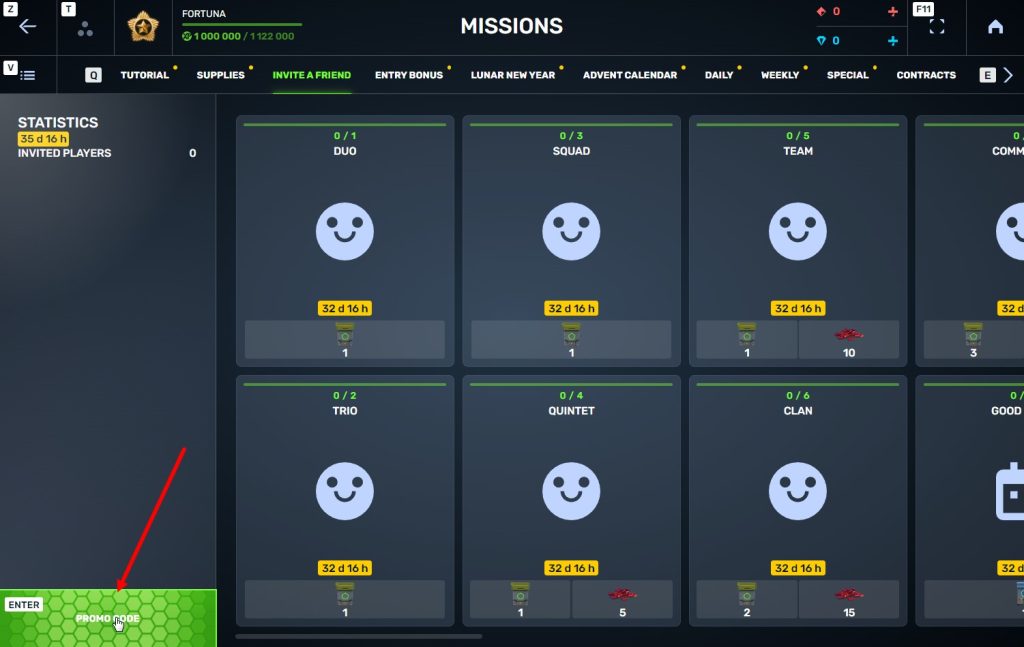

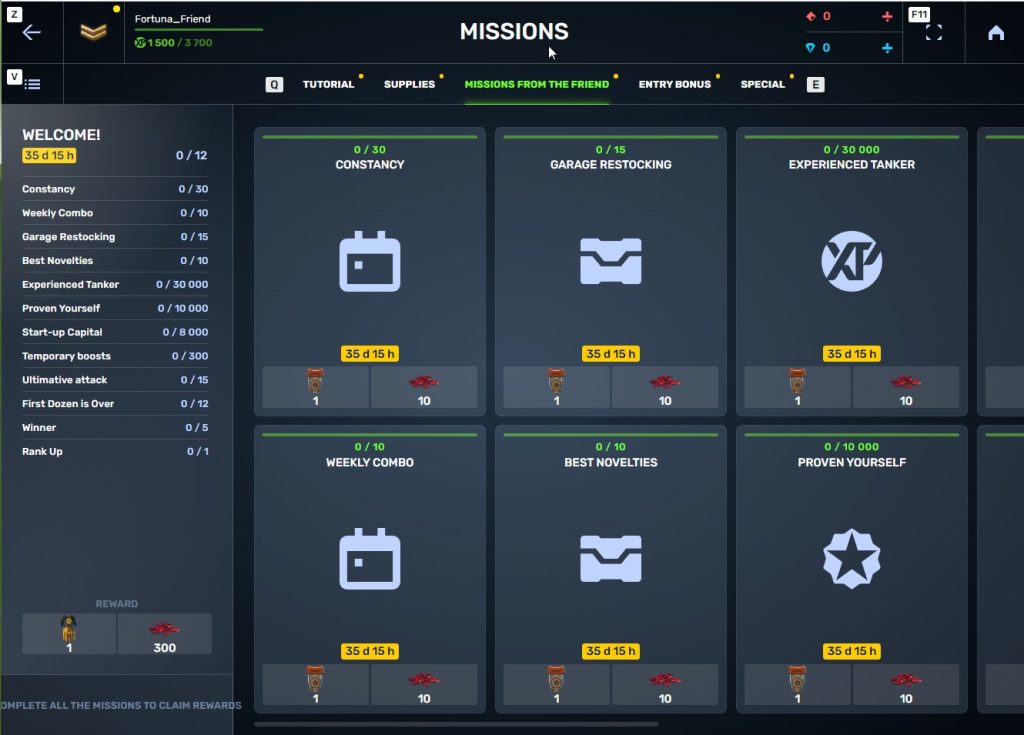

STEP 2 You need to enter the game and go to the Missions menu.

STEP 3 There, you need to open the special «Invite a friend» category of missions.

STEP 4 In that section, you need to generate a special invite promo code.

STEP 5 Share this Promocode with people you want to invite to the game and tell them how they can activate it (read below).

Who can become your referral

There are two types of players who can become your referrals:

- Players who created their account since January 30th 2 AM.

- Player who last entered the game before November 24th 2 AM UTC.

Pay attention to the fact that in order to activate an invite promo code, a player should have at least Private rank.

What do I get for inviting players?

- Once you generate your invite promo code, send it to your friends and acquaintances.

- In the special «Invite a friend» category of missions, you will get a set of special missions.

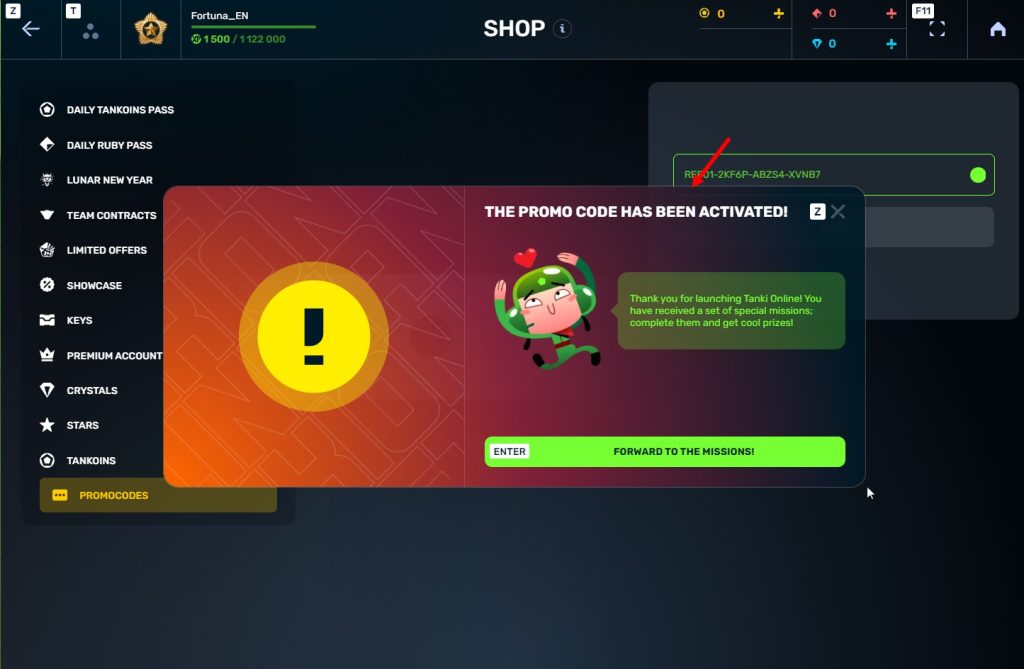

3. Once they activate your promo code, players who have been invited will also get a set of their own special missions in the «Missions from a friend» category. In your «Invite a friend» category you can track how your referrals complete their missions, and thus your missions get completed and you can claim rewards for the efforts of the players you have referred.

Missions for those who invite

There are two types of missions for inviting players. The first type gives you rewards for players who just activated your promo code. The second type gives you rewards once your invited players complete the required missions.

TASK

Invite 1 player to the game.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Invite 2 players to the game.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Invite 3 players to the game.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Invite 4 players to the game.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invite 5 players to the game.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invite 6 players to the game.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invite 7 players to the game.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 10 referral event missions

REWARD

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Invited players completed 20 referral event missions

REWARD

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Invited players completed 30 referral event missions

REWARD

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 40 referral event missions

REWARD

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 50 referral event missions

REWARD

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 60 referral event missions

REWARD

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 80 referral event missions

REWARD

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 1 referral event supermission

REWARD

EPIC KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Invited players completed 2 referral event supermissions

REWARD

EPIC KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 3 referral event supermissions

REWARD

EPIC KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 4 referral event supermissions

REWARD

EPIC KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 5 referral event supermissions

REWARD

EPIC KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 6 referral event supermissions

REWARD

EPIC KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

RUBY

TASK

Invited players completed 7 referral event supermissions

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RUBY

LEGENDARY KEY

How it works for referrals

Once you invite a friend and give them your promo code, your friend should do the following:

STEP 1 Create an account (or log into an existing one, if it meets the criteria)

STEP 2 Get the «Private» rank. It won’t take much time.

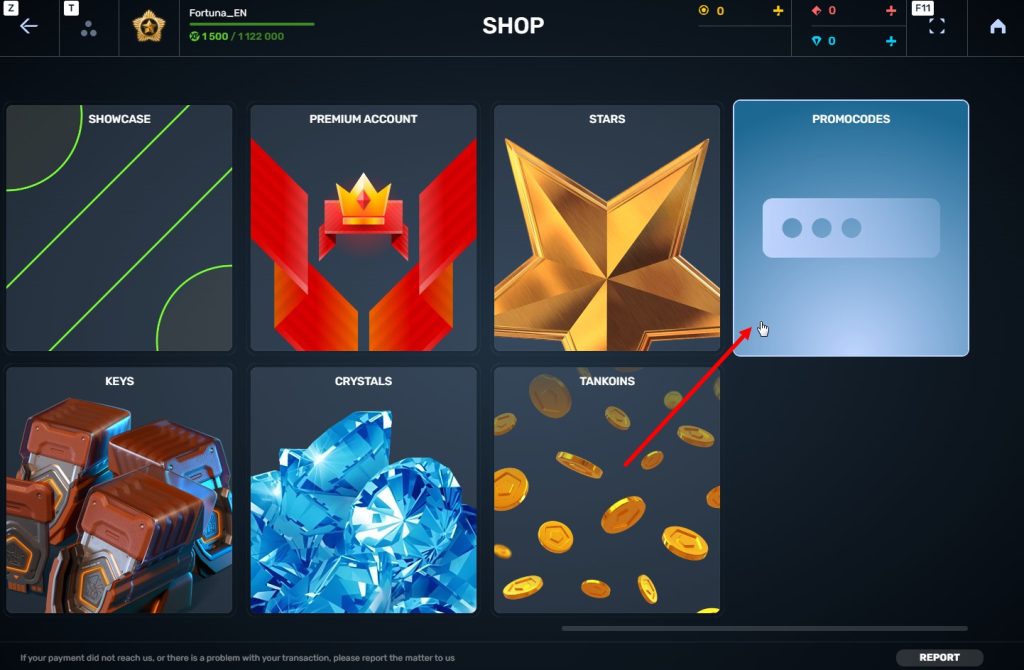

STEP 3 Enter the Shop

STEP 4 Go to the «Promocode» section

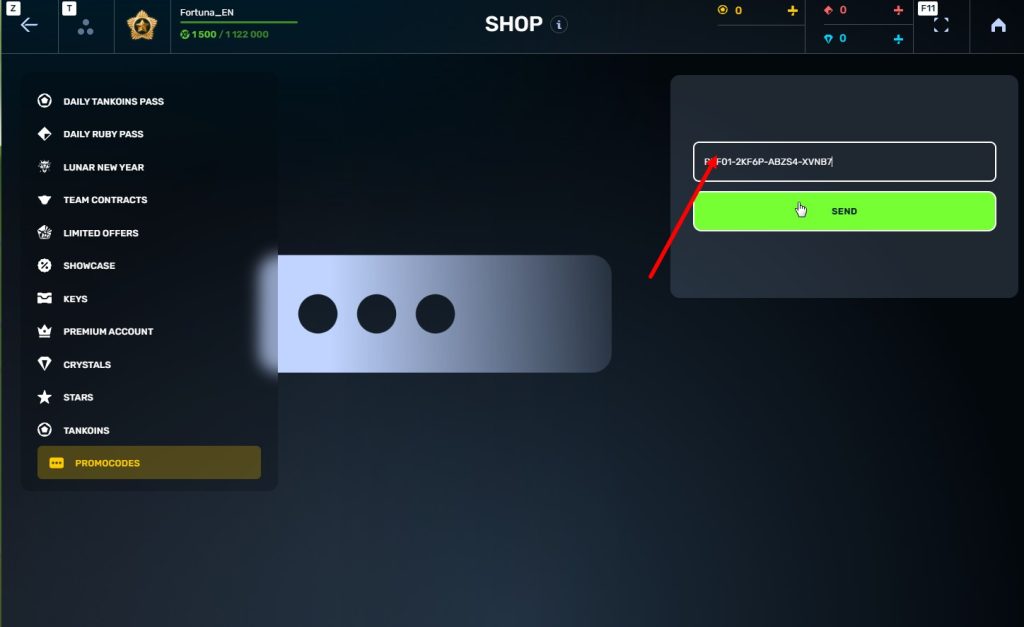

STEp 5 Activate the promo code

STEP 6 Press the «Forward to the missions!» button

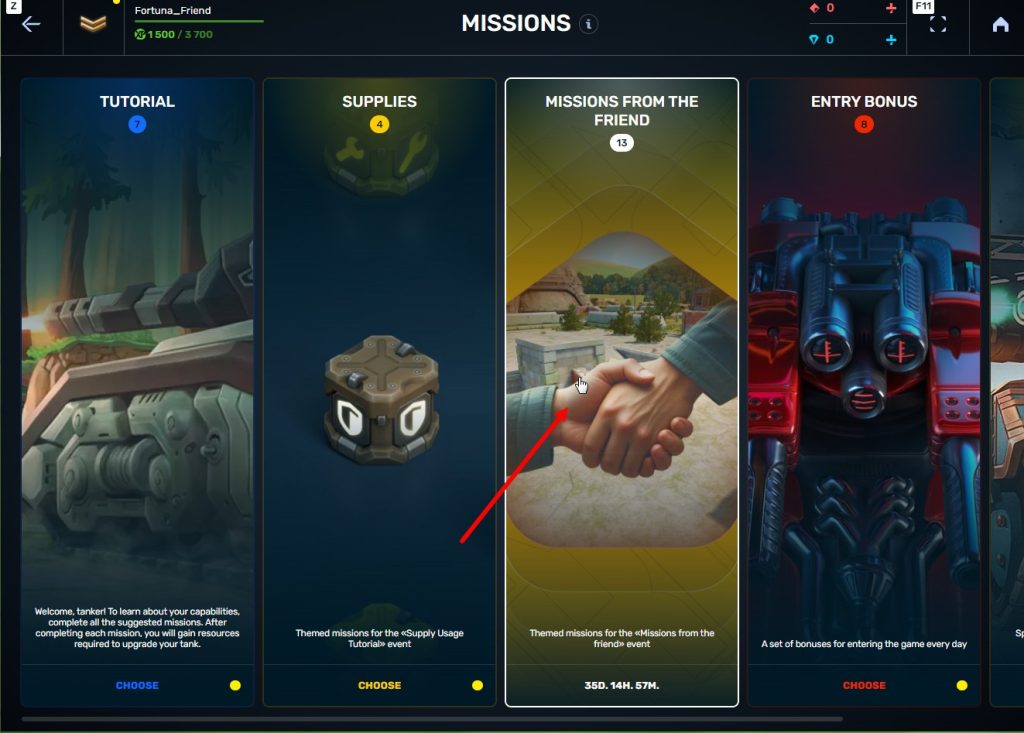

STEP 7 In the Missions menu, there will be a section called «Missions from the friend» with a set of special missions to complete

STEP 8 Complete the missions and claim the rewards

Bonuses for referrals for completing missions

TASK

Supermission. Complete all referral missions.

REWARD

TASK

Complete 30 daily missions.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Complete 15 weekly missions.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Open 15 Common Containers

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Open 10 Epic Containers.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 30 000 experience points.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 15 000 reputation points.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 10 000 crystals.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Activate supplies 300 times.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use overdrive 15 times.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 20 battles.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 5 battles.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Get a new rank.

REWARD

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Invite friends and get rewards!

Nothing unites players like a team, because together we are strong!

How to participate

From January 23rd 2 AM, till February 12th 2 AM UTC, “Team Contracts” will be added into the game.

To participate, you need to purchase a special offer – “First Contract”, which includes the “Event Pass” required for participation.

Factions

Players who purchase the special offer will be assigned randomly into 1 of 4 factions:

A little bit of magic won’t hurt 🙂

Contracts

On each day starting from February 2nd, a new team contract will appear on the event page. A contract is a mission for all the faction members. It is available only for 24 hours.

In the game, participants will see the mission that they must complete.

TASK

Catch 3 gold boxes in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Capture 3 flags in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Destroy 4 tanks using grenades in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Collect 3 nuclear energy boxes in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Destroy 30 tanks using Tesla turret in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Earn 30000 crystals in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Destroy 30 tanks using critical damage in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Destroy 3 Juggernauts in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Destroy 3 tanks using grenades in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

Note

The percentage of players who complete a contract is taken into the count of each faction.

Each faction will receive points for completing missions every day.

The greater the proportion of faction members who have completed the mission, the more points you can get.

- 1st place — 200 points

- 2nd place — 150 points

- 3rd place — 100 points

- 4th place — 50 points

Note:

- Points are added after the game day ends.

- Points are added into the personal player inventory on the event page.

- To receive the points, a player must complete the contract.

Special offers

Another way to receive points is to purchase them in special offers on the event page. The more points you have, the more prizes you can get.

Prizes

Let’s get to the most interesting part – prizes!

After the event ends and up until 2 AM UTC on February 19th, players can exchange their points earned from completing contracts or purchasing special offers for prizes in the event shop.

You just need to select prizes in an amount not exceeding the number of points in your inventory.

Available prizes:

Prizes are added to the account after some time following their purchases on the event page.

Have a good game and try to complete as many contracts as possible!

In today’s episode, we will be launching the Team Contracts event. We’ll also be introducing negative currency balance and discussing ongoing and upcoming events.

Who knows, perhaps it will be you and your team that will achieve the highest results.

Who knows, perhaps it will be you and your team that will achieve the highest results.We also want to remind you that in order to simplify the search for players and teams, we have updated our eSports website and added a special section in which teams search for players, and players search for teams.

Tournament rules

- Ranks: First Sergeant — Legend

- The team consists of 7 players.

- In battle – 5 tankers from each team.

- Your garage doesn’t matter as battles are played in Sport mode.

- On the battlefield, in each team, hulls and turrets should not be repeated. For example, if you use Hornet and Ricochet, no one else from your team should be in the battle with Ricochet or Hornet.

- More detailed rules can be found on the tournament page on the eSports portal.

Prizes

- TMR points

- Unique «Impulse» paint

- 96,000 Rubies

- 88,000,000 crystals

- 2,835 epic keys

- 1,071 days of «Premium Pass»

Tournament dates

- Tournament registration will last from 13:00 UTC on January 12th till 17:00 UTC on January 25th.

- The first match will start on January 26th.

- The tournament will end before February 19th.

- The transfer is open and will last until 17:00 UTC on January 25th.

The tournament will be attended by 32 to 128 teams.

Almost immediately after the first rating tournament, we will announce the second one and after all the rating tournaments there will be a Major one. In the Major tournament, they will fight not only for in-game rewards, but also for real cash.

Go to the eSports portal, create your team, read the rules, register and get ready for the next rating tournament! And if you have any questions, visit our eSports Discord server, they will definitely help you.

See you on the battlefields and eSports broadcasts!

Event dates: January 16th, 2 AM UTC — February 6th, 2 AM UTC.

Bots

During the event, bots in Matchmaking battles will be equipped with special equipment: Freeze, Gauss, Hammer, and Magnum, with the skins from the ICE series!

Now it will be easy to distinguish them from common players!

Discounts

Take advantage of the beneficial discounts from January 16th to January 19th.

For 3 whole days, you will be able to obtain the following items with a 30% discount:

Special Event Modes

During the event, we’ve prepared three special modes for you.

«Dragon’s gold» — one of the players is equipped with the «Juggernaut» super tank

- Iran MM

- Kungur MM

- Magistral MM

This is the game mode for Tanki virtuosos! In addition to well-aimed Grenade throws, you also need well-aimed Railgun shots. An accurate shot at a thrown Grenade and there will be no trace left of your enemy. Shoot, detonate, and win!

- Sandbox Remastered

- Sandal Remastered

- Cross Remastered

Crush enemies with BO-NK in the updated team mode and catch a lot of gold boxes, because this weekend, we have increased their dropping frequency!

- Canyon PRO

- Garder PRO

- Pass PRO

Special offers

What’s any holiday without some great deals at awesome prices?

January 16th — February 2nd

January 16th — February 6th

** For 30 days, each day the player can access a pre-completed mission upon logging in, from which they can claim a reward of 150 Rubies.

Note: One-time purchase

January 23rd — February 6th

January 30th — February 6th

Epic Containers

- SKIN Railgun UT

- SKIN Ares XT

- Railgun’s “Round Destabilization” augment

- Railgun’s “«Death Herald» Compulsator” augment

- Railgun’s “Excelsior” augment

- Ares’ “Excelsior” augment

- Ares’ “Grenadier” augment

- And everything you can get from Common Containers

Special Missions

We have prepared a plethora of exciting missions that will make the event more exciting!

Part 1. January 16th — January 23rd

Part 2. January 23rd — January 30th

Part 3. January 30th — February 6th

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

TASK

Finish 2 battles in the festive mode.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

January 16th — February 6th

TASK

Complete «Come in! Part 1», «Good Reputation. Part 1», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 1», «Frostbite. Part 1», «Cold-Hearted. Part 1», «Freezer. Part 1», «Warm Place», «Ice Shield», «Permafrost», «Shards» and «Ice Stash» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in CP mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use boosted armor 150 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 experience points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 4000 crystals in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Open 15 any Containers.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

January 23rd — February 6th

TASK

Complete «Come in! Part 2», «Good Reputation. Part 2», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 2», «Frostbite. Part 2», «Cold-Hearted. Part 2», «Freezer. Part 2», «Snow Massacre», «Snow Trap», «North Star», «Snowstorm» and «Inevitability» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in TDM mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use mines 150 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 45 stars in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 30 tanks in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Deal 100000 damage in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

January 30th — February 6th

TASK

Complete «Come in! Part 3», «Good Reputation. Part 3», «Choice Without a Choice. Part 3», «Frostbite. Part 3», «Cold-Hearted. Part 3», «Freezer. Part 3», «Northern Flag», «Cold Treatment», «Preemptive Play», «Shock Freeze» and «Spread» missions.

REWARD

EPIC KEY

RARE KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Enter the game at least once.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 5000 reputation points in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 3000 reputation points in Quick Battle mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Finish 10 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Be in the winning team of 2 battles in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Make any purchase in the game’s Shop.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Earn 1000 reputation points in CTF mode in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use repair kit 150 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 1 tank using grenades in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Destroy 10 tanks using critical damage in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

TASK

Use any grenade 10 times in matchmaking battles.

REWARD

COMMON KEY

EXPERIENCE POINTS

Advent Calendar

We are launching the festive advent calendar for you!

After purchasing the “Advent Calendar” special offer, you will get access to:

- 5 standard missions

- 1 Supermission with unique rewards!

All you need to do is log into the game during the event and claim your gifts.

Task: Complete all “One More Day” missions that appear after January 16th.

Completing 5 standard missions will unlock the final Supermission.

Supermission

One more day

Elite Pass

The most luxurious pass is here! It will consist of 20 levels.

Your goal is to earn stars and unlock new levels, and for each level you reach, you will receive additional prizes!

In order to complete the whole pass and reach the main prize, you will need to earn 1000 stars.

All stars earned during the event will be counted. Progress begins with the start of the event. Stars earned before the purchase of the «Elite Pass» will also be counted. The «Elite Pass» itself is required to claim the prizes. By purchasing it, you will be able to claim all the unlocked prizes to your Garage!

The Main Prizes are Legendary Key ×1 and the “Excelsior” augment for Hornet!

The price of this «Elite Pass» is 2300 Rubies.

Festive Decorations

- Festive paint on cargo drones

- Festive paint

- Festive Gold Box drop zone skin

- Special loading screen

- Festive billboards

Great mood and good luck to everyone!

How to get there?

You can get onto “Tanki Classic” only through the announcement window in the main game lobby.

You will only have access if you are an early access participant.

How to get Early Access?

The special Early Access offers for “Tanki Classic” were only available for a limited time. With the start of the mass testing phase, we are bringing these special offers back on sale. This is your chance to become a part of the legendary “Tanki Classic” project ahead of everyone else!

What is there in the game?

This is a test version of the game. It is possible to encounter bugs, issues, unfinished features, and anomalies.

During the test, we will restart the game several times and even temporarily pause the testing process.

We will also wipe the test server database several times, which will reset all your progress.

For testing Tanki Classic, we use new server infrastructure. This may cause unstable server performance during the first weeks of testing. We will be configuring and fixing everything.

Is this early access already?

No. Early access will be announced separately, 2 weeks before the game is released. You will be able to get access to the game earlier than anybody else and progress your account earlier than others.

What is the “Development Plans” section on the Tanki Classic website?

Alongside the launch of Tanki Classic testing, we are adding a special “Development Plans” section to the project’s website. From now on, this section will be the primary, first-source of information on the development of the Tanki Classic project.

There, we will announce the key development areas of the project earlier than anywhere else.

Please note: the presented plans reflect our current goals and may be adjusted based on your feedback and voting results.

In the future, we will launch the promised polls for the game mechanics. You, the players, will define the future of “Tanki Classic!”

Feedback can be left on the forum topic of this news.

Jump to content

Jump to content

Recommended Posts